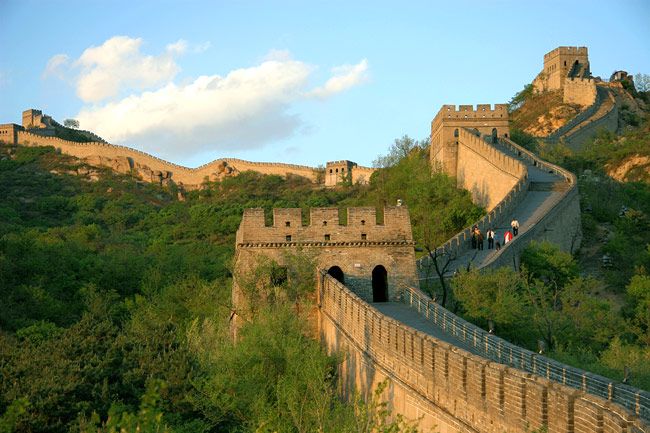

The Majestic Scale of the Great Wall

The Great Wall, stretching an incredible 21,196.18 kilometers, is one of the world's most iconic architectural marvels. Built over centuries, it began with defensive walls from the Warring States period. Emperor Qin Shi Huang later unified these into a single structure, and the Ming Dynasty expanded and fortified it. Each dynasty tailored sections to its strategic needs, creating a vast defense system that evolved. This monumental project highlights ancient China's engineering brilliance and generations of effort to safeguard their homeland.

Distribution and Role of Strategic Passes Along the Great Wall

The Great Wall's significance lies not only in its immense length but also in the strategic placement of its key passes.

-

Shanhai Pass (Shanhaiguan): Known as the "First Pass Under Heaven," it marks the Wall's eastern end. Positioned where land meets the sea, Shanhai Pass served as a natural barrier and a crucial military stronghold during the Ming Dynasty. It effectively blocked invasions from the northeast while acting as a key transportation hub between central China and the northeast.

-

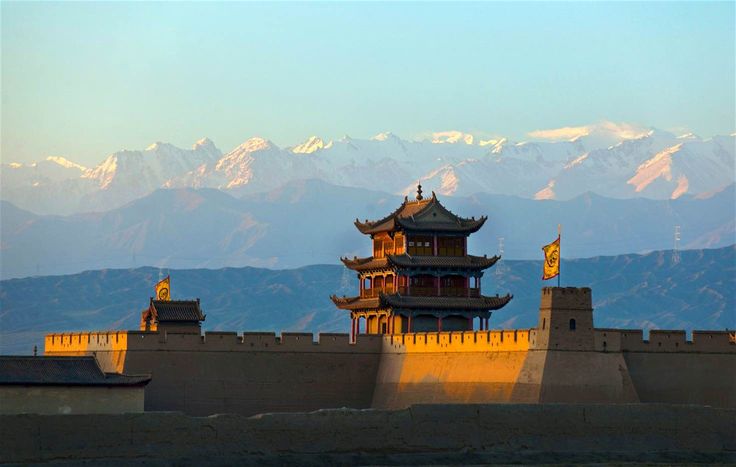

Jiayu Pass (Jiayuguan): Located at the western edge of the Wall on the Gobi Desert, Jiayuguan is hailed as the "Mighty Pass Under Heaven." It was both the last line of defense in the Great Wall system and a vital point on the ancient Silk Road. It guarded the gateway between central China and the western regions, playing a significant military and economic role.

-

Other Passes: Throughout the Wall, passes like Juyongguan, Piantouguan, and Zijingguan were built in mountainous areas, leveraging natural terrain to create formidable defense points. These strongholds, with their strategic locations and robust construction, were central to the Wall’s defensive strategy.

Each pass, whether Shanhai's coastal fortifications or Jiayu's desert resilience, reflects the Wall's role as a dynamic defense system throughout Chinese history.

The Long History of the Great Wall’s Construction

The construction of the Great Wall spans over 2,000 years, with contributions from various Chinese dynasties, each adding to this monumental project based on their historical needs.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, feudal states built independent walls to defend against neighboring attacks. These early walls, primarily made of tamped earth, were simpler in design but laid the foundation for future construction.

After unifying China, Emperor Qin Shi Huang connected these separate walls to create the first unified Great Wall, stretching east to west. Its primary purpose was to defend against northern nomadic invasions, especially from the Xiongnu tribes.

In the Han Dynasty, the Great Wall's role expanded with the opening of the Silk Road. It not only served as a military defense but also protected vital trade routes. The construction of watchtowers and relay stations during this period enhanced its functionality.

By the Ming Dynasty, the Great Wall reached its zenith. Faced with significant threats from northern nomadic powers, the Ming government undertook extensive expansions and fortifications. Using bricks and stones, they built a more durable and complex structure, including walls, passes, towers, and beacon systems. These innovations marked a significant leap in architectural and defensive design.

From its humble beginnings to its peak during the Ming Dynasty, the Great Wall reflects China's historical evolution, serving as both a defensive stronghold and a testament to its enduring legacy.

Diverse Architectural Features of the Great Wall

The Great Wall is more than a simple wall—it is an integrated defensive system composed of walls, watchtowers, passes, and outposts, working together to form an impenetrable barrier.

-

Walls: The core structure, stretching across the entire length, served to block direct invasions. Early walls were primarily made of tamped earth, but by the Ming Dynasty, bricks and stones were widely used, making the walls sturdier and better suited for complex military needs.

-

Beacon Towers: Built at elevated points or open areas along the wall, these towers were vital for communication. By lighting smoke signals or fires, they transmitted military alerts across vast distances, functioning as an ancient "high-speed communication network."

-

Passes: Strategic hubs like Shanhai Pass and Jiayu Pass were located at critical points such as valleys and mountain passes. These not only served as military strongholds but also controlled trade, collected taxes, and monitored goods, becoming centers of economic and political activity.

-

Adaptation to Terrain: The design of the Great Wall varied with the landscape. In mountainous regions, it snakes along ridges to create a natural barrier. On plains, the walls were built thicker for extra protection. In deserts, simpler constructions provided both defense and guidance.

This architectural diversity not only enhanced the defensive capabilities of the Great Wall but also showcased the ingenuity of ancient Chinese architects. It stands as a testament to their ability to adapt to different environments and create one of history’s most remarkable engineering marvels.

The Wisdom of the Great Wall’s Materials

The choice of materials for the Great Wall showcases not only advanced ancient engineering but also a keen ability to adapt to local conditions. Each section utilized materials suited to its environment, achieving a perfect balance between durability and resource efficiency.

-

Eastern Regions: With abundant resources and higher rainfall, bricks and stones were used to construct robust, erosion-resistant walls. By the Ming Dynasty, brickmaking and stone-cutting techniques had advanced significantly, enabling the creation of solid and enduring structures. Some sections even included stone staircases, reflecting meticulous design for both defense and logistics.

-

Western Regions: In the arid deserts and Gobi, where stone was scarce, rammed earth was the primary material. This technique compacted layers of soil into dense walls, which proved economical and effective in dry climates. However, these walls were vulnerable to erosion in wetter conditions, resulting in less preservation compared to eastern sections.

-

Resource Adaptation: Builders also ingeniously incorporated local resources. For example, river areas used pebbles for reinforcement, while forests provided timber for fences and temporary structures. This minimized transportation costs and ensured structural stability.

These material choices highlight ancient Chinese ingenuity in adapting construction to natural surroundings, enabling the Great Wall to stand as a timeless symbol of resilience and resourcefulness.

The Starting and Ending Points of the Great Wall

The Great Wall's starting and ending points define its vast expanse and carry deep historical significance.

-

Starting Point: Shanhai Pass (Shanhai Guan) Located in Qinhuangdao, Hebei Province, Shanhai Pass is known as the "First Pass Under Heaven." This is the only part of the Great Wall that meets the sea, creating a natural barrier where land and water converge. Historically, it was a crucial defense point against northern nomads and served as a cultural and trade hub connecting the Central Plains with Northeast China.

-

Ending Point: Jiayu Pass (Jiayu Guan) Situated on the Gobi Desert in Gansu Province, Jiayu Pass marks the western terminus of the Ming-era Great Wall. Dubbed the "Strongest Pass Under Heaven," it was both a formidable defense structure against invasions from the northwest and a key node on the Silk Road. Its grand design, with towering walls and sturdy watchtowers, highlights its military and architectural significance. Jiayu Pass also played a pivotal role in facilitating cultural and economic exchange between China and the West.

These two landmarks, one in the east and one in the west stand as enduring symbols of the Great Wall's historical, cultural, and strategic importance, like two shining jewels safeguarding China's rich legacy.

A Blend of Culture and Legends

The Great Wall is not only a testament to ancient Chinese military ingenuity but also a wellspring of captivating legends that enrich its cultural significance.

-

Meng Jiangnu’s Lament: The most famous tale is that of Meng Jiangnu, whose husband was conscripted to build the Wall and tragically died from the grueling labor. Overcome with grief, she journeyed to find him, and her sorrowful cries caused a section of the Wall to collapse. This story reflects compassion for the hardships endured by laborers and critiques the societal toll of such monumental projects.

-

The Iron Ox Legend: Another story speaks of an "iron ox" buried beneath a river to stabilize a section of the Wall frequently damaged by floods. The mythical iron ox symbolizes human ingenuity and determination to overcome natural challenges.

These legends blend human emotion, cultural values, and imaginative storytelling, adding depth to the Great Wall’s historical and cultural heritage while inspiring endless curiosity and reflection in future generations.

The Global Influence of the Great Wall

The Great Wall, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, holds immense historical and cultural significance as a window into China's rich history and civilization. Its vast scale, ancient origins, and profound cultural value have earned worldwide recognition, symbolizing the ingenuity and resilience of the Chinese people in military strategy, architecture, and cultural heritage.

Today, the Great Wall draws millions of visitors annually, captivating them with its majestic views and historical depth. Whether trekking along its winding paths or exploring its imposing passes, tourists experience its grandeur and cultural significance firsthand. Moreover, the Wall serves as a bridge between Eastern and Western cultures, fostering greater understanding and collaboration through tourism and cultural exchange. It stands as a powerful symbol of global heritage and shared human achievement.